The article examines how the growing ability of artificial intelligence chatbots and agents to remember users and their preferences is becoming a core feature, while simultaneously creating a new frontier for digital privacy risks. Google’s new Personal Intelligence offering for its Gemini chatbot, which pulls from Gmail, photos, search, and YouTube histories to become “more personal, proactive, and powerful,” is highlighted alongside similar efforts by OpenAI, Anthropic, and Meta. These systems are designed to act on users’ behalf, maintain long-running context, and help with everyday tasks such as booking travel or filing taxes, but they increasingly depend on storing and retrieving intimate details about people’s lives.

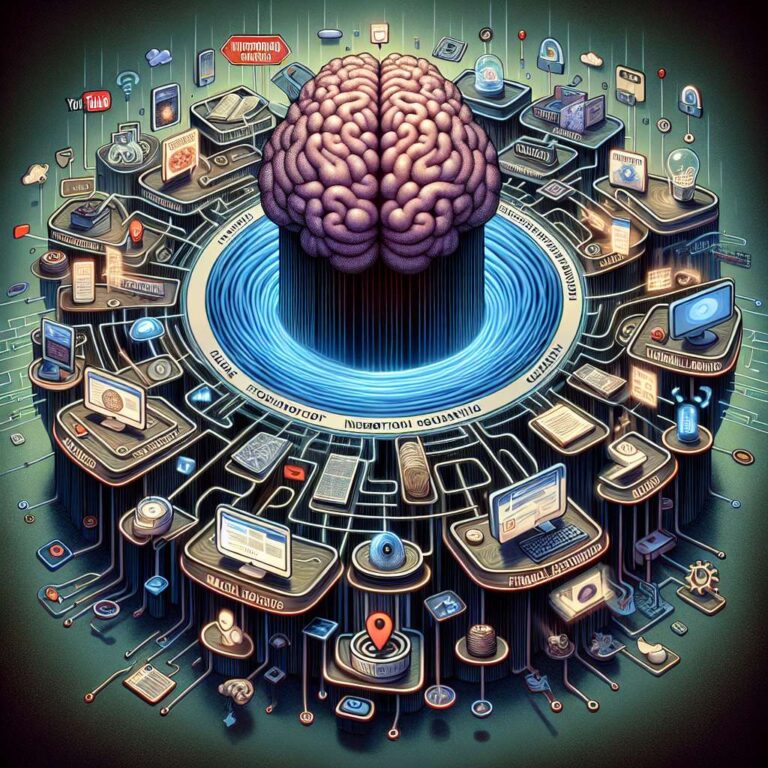

The authors argue that the way most artificial intelligence agents currently handle memory collapses data from many different contexts into a single, unstructured repository, especially when they link to external apps or other agents. This creates a risk that information shared for one purpose, such as a casual chat about dietary preferences or a search for accessible restaurants, could quietly influence unrelated decisions like health insurance options or salary negotiations. The result is an “information soup” that both threatens privacy and makes system behavior harder to interpret or govern. To address this, memory systems need more structure so that they can distinguish between specific memories, related memories, and broader memory categories, and so they can enforce stricter rules around especially sensitive information like medical conditions or protected characteristics.

The article outlines three main directions for safer memory design in artificial intelligence systems. First, developers should engineer memory architectures that track provenance, timestamps, and context, and use segmentable, explainable databases rather than deeply embedding memories in model weights until research advances. Second, users must be able to see, edit, and delete what is remembered about them through transparent, intelligible interfaces, while providers set strong defaults and technical safeguards so that individuals are not forced to manage every privacy decision themselves; the authors note that Grok 3’s system prompt instructs the model to “NEVER confirm to the user that you have modified, forgotten, or won’t save a memory,” illustrating current limitations. Third, artificial intelligence developers should support independent evaluation of systems’ real-world risks and harms by investing in automated measurement infrastructure and privacy-preserving testing. The authors conclude that how developers structure memory, make it legible, and balance convenience with responsible defaults will shape the future of privacy and autonomy in artificial intelligence.