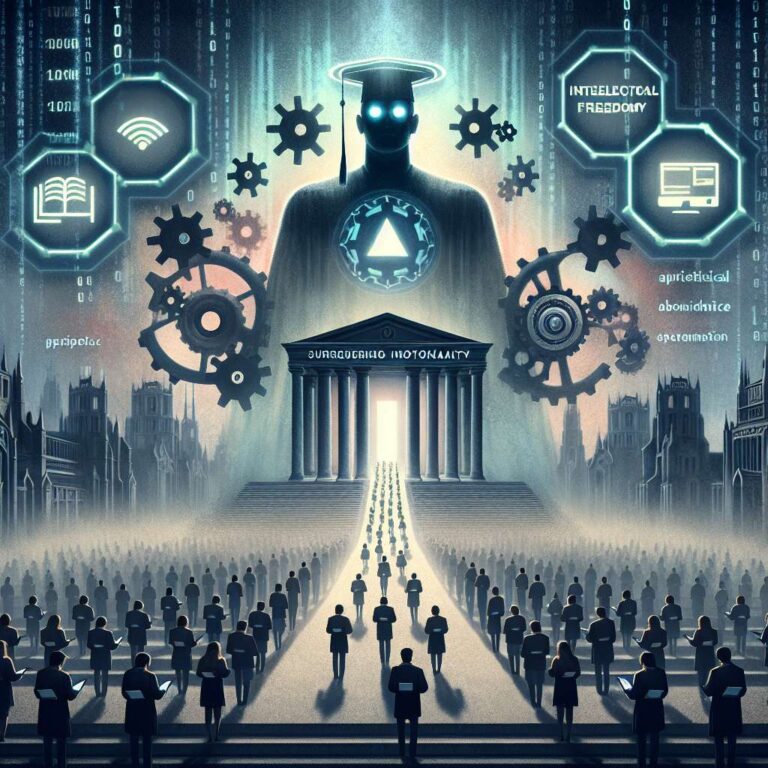

Universities risk surrendering intellectual autonomy to Silicon Valley as they rush to adopt Artificial Intelligence systems, according to Bruna Damiana Heinsfeld, an assistant professor of learning technologies at the University of Minnesota. In an essay for the Civics of Technology Project, she argues that colleges are allowing big tech companies to reshape what counts as knowledge, truth, and academic value, particularly when technological tools are bundled with the identity and branding of the corporations behind them. As leaders race to appear “Artificial Intelligence-ready,” she contends that higher education is drifting away from critical inquiry toward compliance with corporate logics.

Heinsfeld describes Artificial Intelligence not just as a neutral tool but as a worldview that elevates efficiency, scale, and data as primary measures of truth and value. When universities adopt these systems without serious scrutiny, she warns they risk teaching students that big tech’s logic is not only useful but inevitable. She cites California State University as an example, noting that the institution signed a $16.9 million contract in February to roll out ChatGPT Edu across 23 campuses, providing more than 460,000 students and 63,000 faculty and staff with access to the tool through mid-2026. She also points to an AWS-powered “Artificial Intelligence camp” hosted by the university, where students encountered pervasive Amazon branding, from corporate slogans to AWS notebooks and promotional swag, as evidence of how corporate presence can saturate the learning environment.

The concerns extend beyond institutional strategy and into everyday classroom practice, according to Kimberley Hardcastle, a business and marketing professor at Northumbria University in the UK. Hardcastle told Business Insider that generative Artificial Intelligence is quietly shifting knowledge and critical thinking from humans to big tech algorithms, and she argues that universities must redesign assessments for an era in which students’ “epistemic mediators” have fundamentally changed. She advocates requiring students to show their reasoning, including how they reached conclusions, which sources they used beyond Artificial Intelligence, and how they checked information against primary evidence. Hardcastle also calls for built-in “epistemic checkpoints” where students must ask whether a tool is enhancing or replacing their thinking and whether they truly understand concepts or are merely repeating an Artificial Intelligence-generated summary. For Heinsfeld, the central danger is that corporations will come to define legitimate knowledge, while for Hardcastle it is that students will lose the ability to evaluate truth for themselves. Both argue that education must remain a space where students learn to think and to confront the architectures of their tools, or else universities risk becoming laboratories for the very systems they should be critiquing.