The uk government released an ambitious strategy to phase out animal testing, setting near-term targets for specific uses. The plan would end testing of potential skin irritants on animals by the end of next year, expect an end to tests of Botox strength on mice by 2027, and reduce drug tests in dogs and nonhuman primates by 2030. The announcement follows moves by other regulators: the us food and drug administration has a plan to replace animal testing for monoclonal antibody therapies with more human-relevant models, and the european commission is working on a road map after a June 2024 workshop.

The article notes why change is pressing. Animal experiments have been central to scientific discovery and remain mandated by many regulators, but millions of animals are still used each year and roughly 95% of treatments that look promising in animals fail to reach market. That gap, combined with ethical concerns and reluctance among some scientists to participate in animal testing, has driven demand for alternatives that better model human biology.

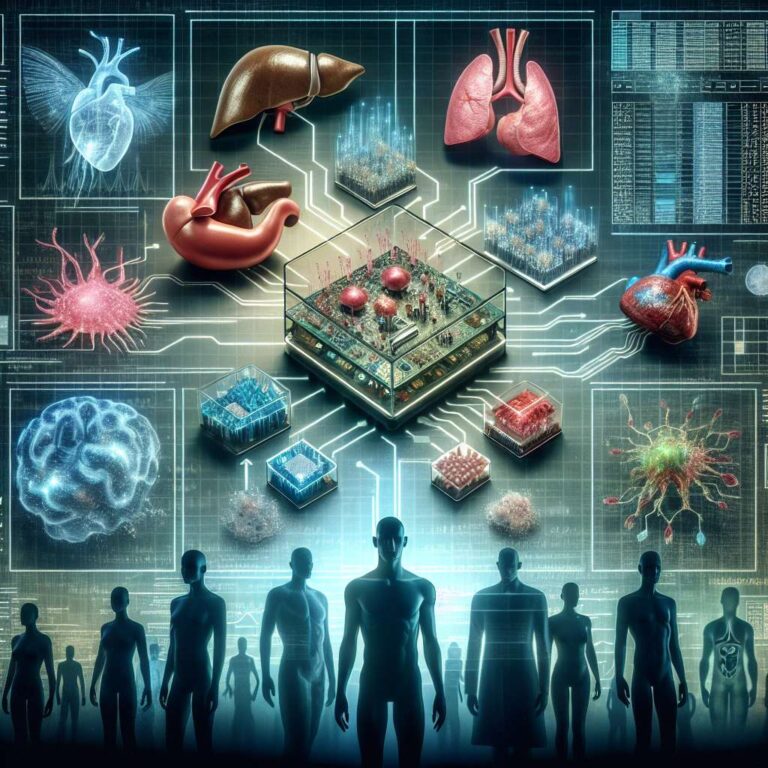

Several technologies are already offering new ways to test therapies without animals. Organs on chips recreate miniature human tissues and have been built for livers, intestines, hearts, kidneys and brain tissue. These chips are being used in real research: heart chips have flown to space, the FDA used lung chips to assess covid-19 vaccines, and gut chips are studying radiation effects. Lab-grown 3D organoids and embryo models let researchers observe development and test drugs, with the potential to personalize models using a patient’s own cells. Efforts to connect multiple chips into a body on a chip continue, though a fully integrated system has not yet been achieved.

Data-driven approaches matter too. The strategy highlights the promise of Artificial Intelligence to parse large datasets, reveal connections between genes and disease, and design new drugs that could be tested on digital reconstructions of humans. Biomedical teams have created digital twins of organs; one trial uses a digital heart to guide surgeons on where to ablate tissue for atrial fibrillation. Despite progress, the article cautions that complete elimination of animal testing by 2030 is unlikely because many regulators still require animal data and current alternatives do not yet fully capture whole-body responses. Still, ongoing advances make a future with far less animal testing increasingly plausible.