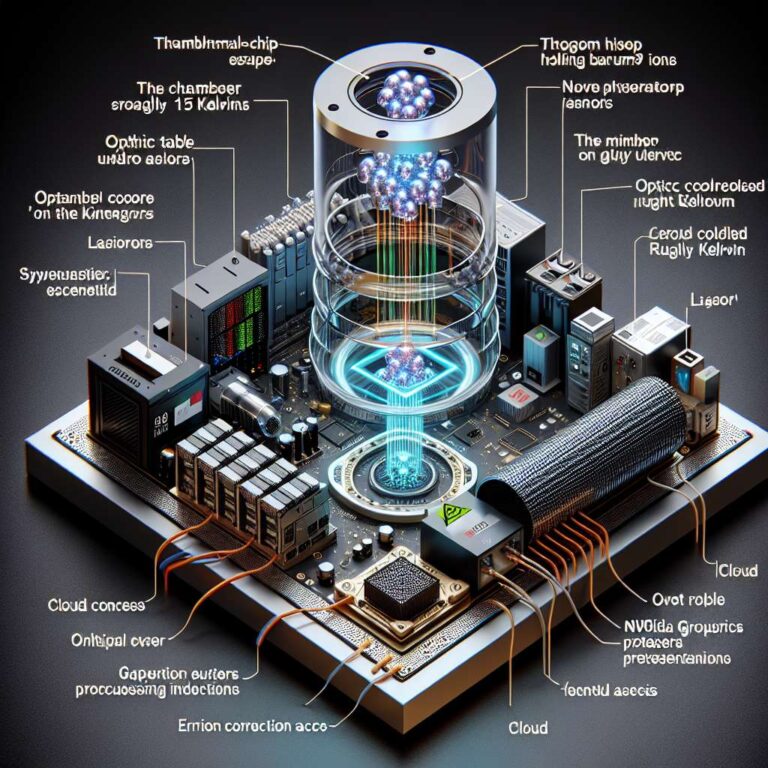

Quantinuum today unveiled Helios, its third-generation quantum computer housed at the company facility in Colorado. The system centers on a thumbnail-size chip holding 98 barium ions that serve as qubits and sits inside a chamber cooled to about 15 kelvin on an optical table. Helios assembles mirrors, lasers, optical fiber and control electronics, and users can access the machine remotely over the cloud. The device succeeds H2, which used 56 ytterbium qubits, with barium chosen because it is easier to control.

Helios encodes information in the ions’ quantum states, enabling superposition and entanglement that quantum computing exploits for certain classes of problems. A key advance Quantinuum highlights is error correction. The company reports that Helios requires two physical ions to produce one logical qubit, a substantially lower overhead than recent superconducting systems. By comparison, in 2024 Google used 105 physical qubits to create a logical qubit, IBM used 12 physical qubits for one logical qubit in 2024, and Amazon Web Services used nine physical qubits for a logical qubit in 2024. Quantinuum says its qubits start with lower error rates, and University of Waterloo physicist Rajibul Islam notes entangling pairs on Helios behaved as expected 99.921 percent of the time, a level he says is unmatched on other platforms.

The design benefit behind that precision is ion mobility. Unlike superconducting qubits fixed to a chip surface, ions on Helios can be shuffled to enable all-to-all connectivity, reducing the intermediate operations needed to connect nonadjacent qubits and lowering the error correction burden. Quantinuum also demonstrated error correction running “on the fly” using Nvidia graphics processing units to identify errors in parallel, a capability the company says improves correction throughput. Quantinuum has used its machines to study magnetism and superconductivity and reported a simulation of electrons in a high-temperature superconductor on Helios’ predecessor. The company plans another Helios at its Minnesota site, is building a 192-qubit prototype called Sol for 2027, and aims to deliver a multi-thousand-qubit, fully fault tolerant machine named Apollo in 2029. Despite these advances, Helios and current machines are not yet powerful enough for wide commercial applications such as materials discovery or financial modeling.