Omar Yaghi’s early years in a water-scarce Palestinian neighborhood of Amman, Jordan, where his family had no electricity or running water and relied on taps that flowed at least once every two weeks, left him acutely aware of how fragile access to water can be. Tasked as a child with topping up the family tanks and tracking how much food and water cattle consumed for his father’s butcher shop, he developed a work ethic centered on precision and completion. A chance encounter at age 10 with a chemistry textbook, and its images of molecules as balls and sticks, set him on a path that eventually led to a postdoctoral program at Harvard University and a career building new molecular architectures.

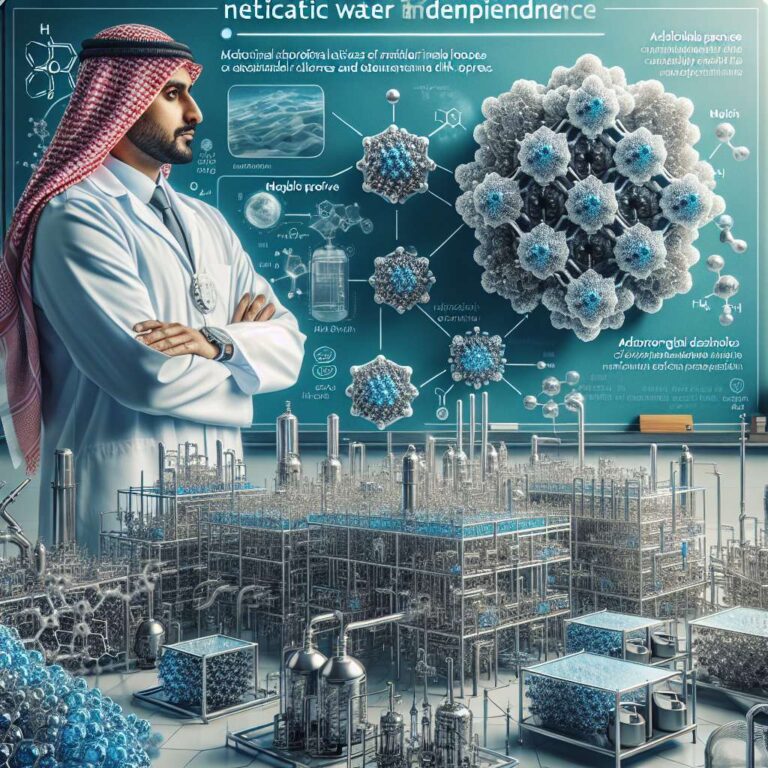

In October 2025, Yaghi was one of three scientists who won a Nobel Prize in chemistry for identifying metal organic frameworks, or MOFs, which are metal ions tethered to organic molecules that form repeating structural landscapes. Initially, he and his team explored MOFs for absorbing climate-damaging carbon dioxide or storing hydrogen, but in 2014 researchers at UC Berkeley realized that the tiny pores in MOFs could be tuned to pull water molecules from air like a sponge and then, with a little heat, release that water. Just one gram of a water absorbing MOF has an internal surface area of roughly 7,000 square meters, and Yaghi’s company Atoco is now racing to demonstrate machines that can produce clean, drinkable water almost anywhere on Earth, including designs that can operate completely off grid without any energy input. He sees this as a way to replace or augment conventional desalination, which dominates in places like Israel and the United Arab Emirates but consumes large amounts of energy and discharges ecologically harmful brine.

Atmospheric water harvesting has deep historical roots, with archaeological evidence of fog collection dating back as far as 5000 BCE and dew harvesting used by ancient Greeks and the Inca, and today analysts say it is a business already worth billions of dollars that is projected to be worth billions more in the next five years. Modern approaches include refrigeration based systems like those from Israel based Watergen, which uses compressors and heat exchangers to wring water from air at humidity levels as low as 20%, and desiccant based systems such as Source Global’s solar powered units, but both require significant energy. MOF based systems promise lower energy demands, drawing water into porous materials that can be regenerated with sunlight, and competitors like AirJoule are already deploying MOF based generators in Texas and the United Arab Emirates, highlighting the potential in places such as Maricopa County, which uses 1.2 billion gallons of water from its aquifer every day and another 874 million gallons from surface sources like rivers. Yaghi and Atoco, leveraging his role as inventor of the material class, envision industrial scale MOF units producing thousands of liters per day and smaller passive devices for remote, off grid use, aiming to give people “water independence” so they are no longer dependent on centralized systems or other parties for their lives.