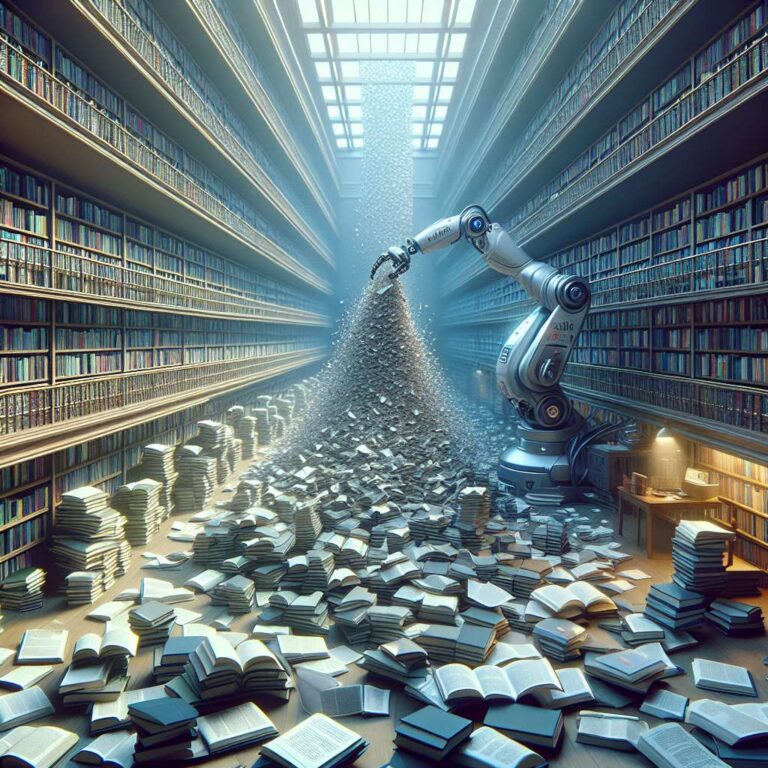

Large-scale analyses of research output suggest that Artificial Intelligence is reshaping science in ways that favor speed and volume over depth and diversity. A study in Nature that examined 41 million research papers across the natural sciences found that scientists who adopt Artificial Intelligence tools publish three times more papers and receive nearly five times more citations, yet the collective range of scientific topics under investigation shrinks by nearly 5 percent and researchers’ engagement with one another’s work drops by 22 percent. A separate Science study of over two million preprints reported that large language model use is associated with posting 36 to 60 percent more manuscripts, but for such papers, greater writing complexity is now correlated with lower publication probability, suggesting a surge in polished but potentially shallow work. Parallel research on Artificial Intelligence-assisted writing in other domains shows a homogenizing effect, including a study of over 2,000 college admissions essays where each additional human-written essay contributed more new ideas than each additional Artificial Intelligence-generated essay, with the gap widening as more essays were analyzed.

These trends interact with long-standing structural pressures inside the scientific enterprise. Researchers in many fields must secure their own funding through grants with success rates of around 10 percent, pushing them to keep a constant stream of applications and papers in progress while institutions evaluate them using publication counts, grant dollars, and citation metrics that measure production rather than genuine progress. Under these conditions, scientists are pushed toward risk-averse, incremental projects that reliably yield papers but rarely transform understanding, a concern echoed in a Pew survey where 69 percent of AAAS scientists said that a focus on projects expected to yield quick results has too much influence on the direction of research. Artificial Intelligence systems that excel at processing existing data and automating writing fit neatly into this incentive structure, concentrating work on data-rich topics and encouraging “scientific monocultures” in which researchers rely on the same tools trained on the same data, leading questions and methods to converge while fostering unwarranted trust in confident outputs derived from datasets many scientists no longer fully engage with.

The deeper bottlenecks, however, are organizational rather than technological. In a candid assessment of the United States biomedical funding system, former NIH official Mike Lauer noted that scientists spend roughly 45 percent of their time on administrative requirements rather than doing science, that grant applications have expanded from four pages in the 1950s to over one hundred today, and that the average age at which a scientist receives their first major independent grant is now 45. These burdens stem in part from a Depression-era funding model centered on small, short-term project grants that treat scientists like vendors competing for construction contracts, forcing them to predict discoveries years in advance and stick to rigid plans in a domain where hypotheses often fail and breakthroughs arise from following curiosity. Artificial Intelligence has already contributed to advances in areas like protein biology and nuclear fusion when targeted at specific scientific problems, but its broad deployment as a generic productivity tool risks accelerating paper production without altering the misaligned incentives that govern careers and funding, akin to adding lanes to a highway when congestion is actually caused by a tollbooth that has never been questioned.