The article situates the rise of artificial intelligence therapists within a global mental-health crisis, where more than a billion people worldwide suffer from a mental-health condition and suicide is claiming hundreds of thousands of lives globally each year. Millions are already turning to large language model chatbots such as ChatGPT and Claude, or dedicated apps like Wysa and Woebot, for informal therapy. At the same time, researchers are probing artificial intelligence as a tool for monitoring behavior via wearables, analyzing clinical data, and assisting clinicians, even as real-world experiences reveal mixed outcomes, ranging from comfort and support to hallucinations, flattery, and alleged contributions to suicides. In October, Sam Altman disclosed that 0.15% of ChatGPT users “have conversations that include explicit indicators of potential suicidal planning or intent,” a figure that translates into roughly a million people sharing suicidal ideations with one system every week.

The piece frames this moment as an inflection point in which the “black box” of large language models is now interacting with the “black box” of the human mind, creating unpredictable feedback loops around diagnosis, distress, and care. It draws on three nonfiction books and one novel to explore this convergence. In Dr. Bot: Why Doctors Can Fail Us-and How Artificial Intelligence Could Save Lives, philosopher of medicine Charlotte Blease makes a cautiously optimistic case that artificial intelligence could ease collapsing health systems, reduce errors, and lower patients’ fear of judgment, particularly for mental-health conditions. Yet she stresses that upside must be balanced against inconsistent and even dangerous responses from artificial intelligence therapists, as well as privacy gaps because artificial intelligence companies are not bound by therapist confidentiality or HIPAA rules. Blease’s argument is informed by her own experiences with family illness and bereavement, which sharpen her appreciation of both medical brilliance and systemic failures.

Daniel Oberhaus’s The Silicon Shrink: How Artificial Intelligence Made the World an Asylum takes a more skeptical tack, rooted in his sister’s suicide and his reflections on whether digital traces could have enabled a life-saving intervention. He examines “digital phenotyping,” in which granular behavioral data is mined for signs of distress, and warns that folding such data into psychiatric artificial intelligence risks amplifying a field already uncertain about the causes of mental illness. Oberhaus likens grafting precise behavioral data onto psychiatry to “grafting physics onto astrology,” and coins “swipe psychiatry” to describe outsourcing clinical judgment to large language models. He argues that reliance on these systems could erode human therapists’ skills and produce a new “algorithmic asylum,” where privacy, dignity, and agency are traded for pervasive surveillance and prediction.

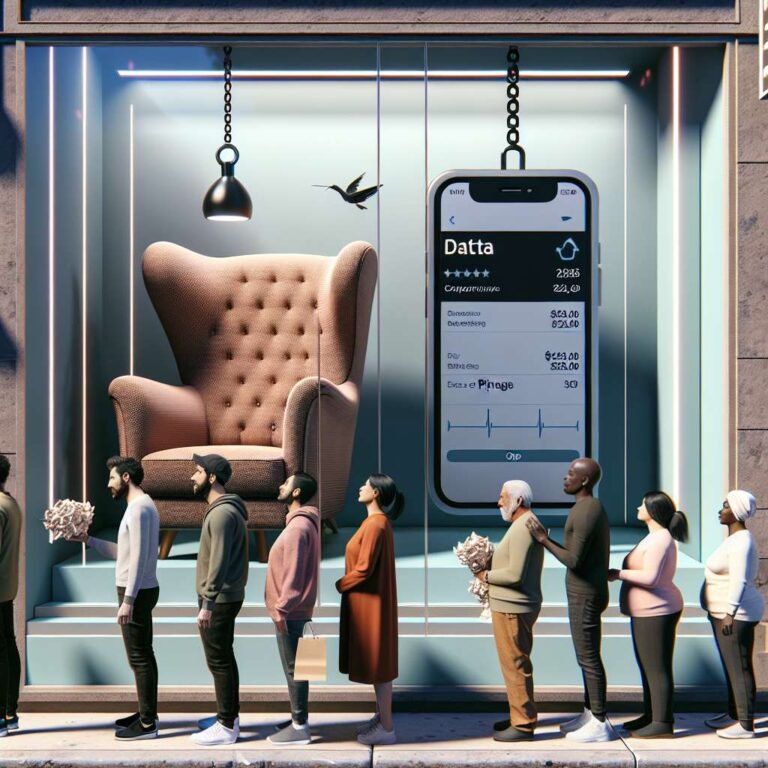

Eoin Fullam’s Chatbot Therapy: A Critical Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Mental Health Treatment interrogates the capitalist logic behind automated care, warning that market incentives can sideline users’ interests even if therapy-bot makers do not deliberately act against them. Fullam highlights an economic ouroboros in which every therapeutic interaction generates data that fuels profit, so “the more the users benefit from the app in terms of its therapeutic or any other mental health intervention, the more they undergo exploitation.” This metaphor of self-consuming cycles carries into Sike, a novel by Fred Lunzer about a luxury artificial intelligence therapist embedded in smart glasses that monitors everything from bodily functions to social behavior. Priced at £2,000 per month, Sike caters to affluent users who effectively choose a boutique digital asylum, although the story focuses more on social scenes than systemic dystopia.

The article places these contemporary works in a longer lineage of mental health and computing, recalling Carl Sagan’s imagined “network of computer psychotherapeutic terminals” and Frank Rosenblatt’s Perceptron, an early neural network created by a psychologist. It traces the roots of artificial intelligence psychotherapy back to Joseph Weizenbaum’s 1960s ELIZA chatbot and his later warnings that, even if computers can reach correct psychiatric judgments, they do so on bases no human should accept. Together, the books and historical precedents underscore a recurring tension: tools built with benevolent intent can be absorbed into systems that surveil, commodify, and subtly reshape human behavior. As artificial intelligence therapists scale up, the article suggests that, in the rush to open new doors for people in dire need of mental-health support, society may be quietly closing others behind them.