Paul Mason identifies two urgent sources of economic instability: a massive and irrational concentration of capital in Artificial Intelligence, and a looming, generalized government debt crisis. He argues that the state is unlikely to bail out Wall Street, Silicon Valley or retail investors in the next crash because public finances are already strained by rearmament and the limits of further debt-driven growth.

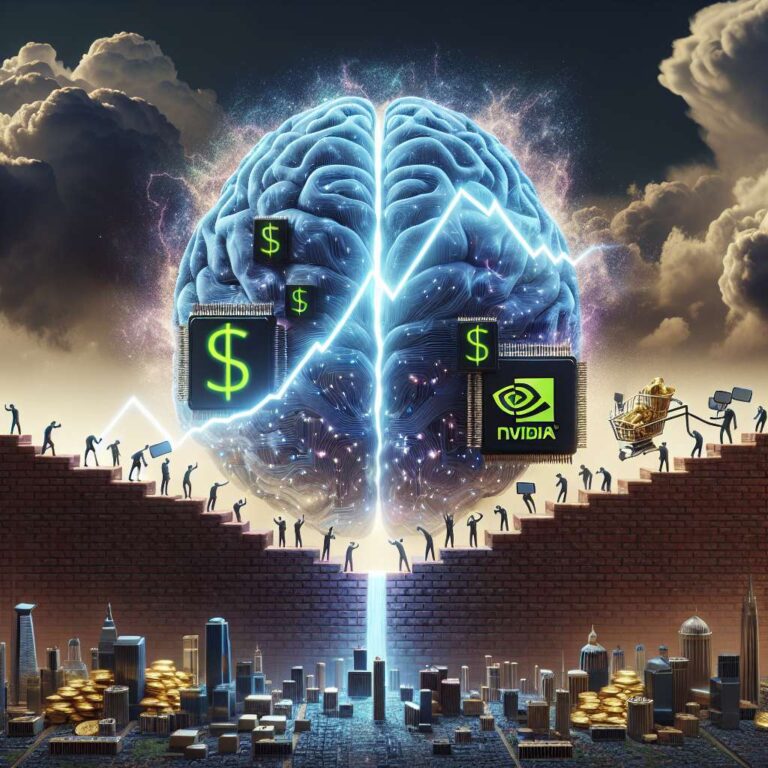

He describes a circular flow of capital centered on Nvidia and cash-rich states such as Saudi Arabia. Nvidia sells expensive chips whose costs, as the Financial Times has noted, may not be recouped before obsolescence, then recycles profits into established firms like AMD, Intel and Oracle, and invests in OpenAI. Capital and performance are heavily concentrated in the Magnificent Seven, with price to earnings ratios above 50 and an outsized share of profits, capital expenditure and market gains, according to Apollo Global Management. The Financial Times’ Bryce Elder argues that even some hyperscaler revenues at Google, Meta, Amazon and Microsoft reflect monopoly rent seeking in markets where newcomers are undercutting prices. A plausible bursting path, Mason writes, could start with weak model progress, a funding dry-up, or a risk miscalibration that pushes large language model vendors into insolvency, hitting hyperscaler revenues, triggering a stock selloff and a flight to safety.

Central banks have started to warn, including the Bank of England, and Mason urges governments to push pension funds to stress test for crash scenarios. Yet he contends bailouts are implausible because sovereign balance sheets are already stretched. Bond yields that were near zero early in the decade now sit around 3 to 5 percent for many developed countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, reflecting investor fears of inflation or financial repression, as The Economist’s Henry Curr notes. The International Monetary Fund’s Gita Gopinath argues the global savings glut has ended, giving way to a bond glut. Savings ratios are down and global debt to GDP is projected to reach 100 percent by 2030, with the United States and parts of western Europe already near wartime levels before factoring in climate, aging and defense costs.

If a flight to safety begins, Mason sees only two destinations: gold and government bonds. Markets will then judge whether governments can use cheaper borrowing to prevent recession from deepening into depression. He situates this moment within broader limits to capitalism: the costly transition away from carbon, demographic aging, and the fragmentation of the rules-based order. Finally, he revisits a Postcapitalism thesis in which information technology’s near-zero reproduction costs and automation of mental tasks favor ultra-monopolies and disrupt the usual reinstatement of labor. The case does not hinge on achieving artificial general intelligence, he says, though many economists now use that possibility to frame the system’s endgame.