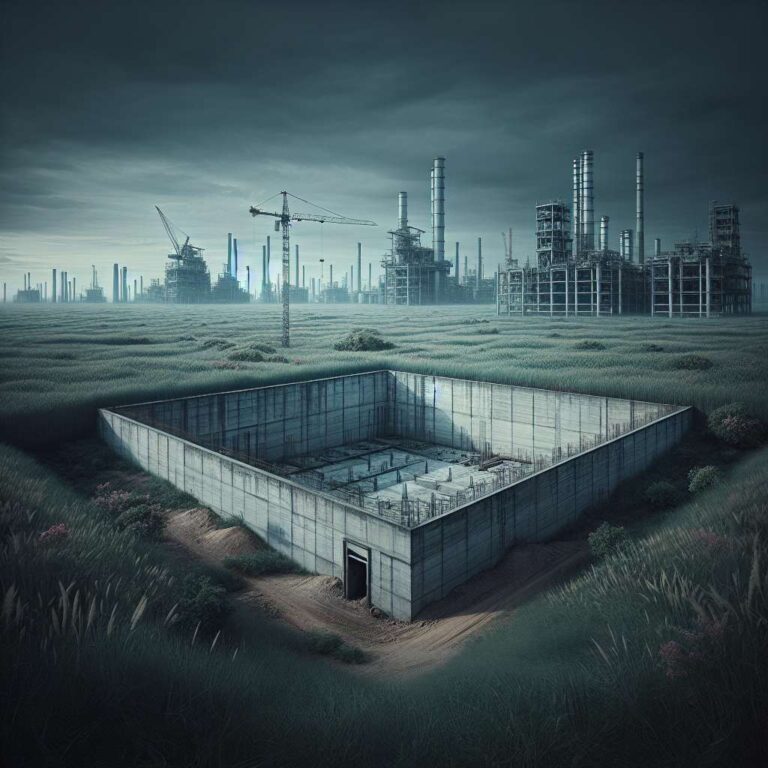

Intel has confirmed a two-year postponement for its highly anticipated semiconductor factory in Magdeburg, Germany, disrupting the country’s ambitious plans to bolster its role in the global chip supply chain. The decision follows the company’s disappointing second-quarter 2024 results, which saw sales dip by 1 percent and a reported per-share loss. In response, Intel launched a sweeping cost-cutting initiative including workforce reductions of over 15 percent, with completion of these measures expected by the end of 2024.

This delay casts uncertainty over Germany’s flagship semiconductor project, which had promised to deliver around 3,000 jobs to the Saxony-Anhalt region. The Magdeburg plant, which forms part of the European Union’s broader semiconductor strategy to capture 20 percent of world production by 2030, now faces both logistical and political turbulence. While initial announcements claimed the factory would remain unaffected, Intel’s confirmation of the delay has prompted state officials to consider alternative plans, including potentially marketing the site to other industries should the project not proceed.

The postponement is rooted in Intel’s struggle to regain a competitive edge—particularly its slow progress in developing specialized chips for Artificial Intelligence. This lag has made it difficult to keep pace with industry leader Nvidia. The German federal government’s €9.9 billion subsidy commitment for the plant has faced criticism given the volatile, capital-intensive nature of the chip business and questions about meaningful domestic research benefits. As the region pins hopes on semiconductor growth, skepticism remains: Ifo President Clemens Fuest pointed to cyclical demand and rapid shifts in investment as inherent risks, suggesting the rationale for state aid may be flawed.

Meanwhile, Europe’s semiconductor agenda presses forward elsewhere, with Taiwanese giant TSMC moving ahead in Dresden and expecting to commence production in 2027. Yet, with one of its core projects in limbo, the EU’s strategy to reduce dependence on Asian chip supply chains—referred to by chancellor Olaf Scholz as the ‘petroleum of the 21st century’—confronts fresh obstacles and possible delays in achieving its technology sovereignty goals.