In Nevada’s high desert, east of Reno, a massive construction effort is underway as some of the world’s largest tech companies and data center operators—including Google, Microsoft, Switch, EdgeCore, Novva, Vantage, PowerHouse, and potentially OpenAI—develop sprawling campuses in the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center. This business park, larger than Detroit, has become the epicenter of a data center gold rush, spurred by the explosive demand for computing power to support Artificial Intelligence and cloud services. Apple is expanding its nearby facility, while Microsoft and other major players are acquiring huge tracts of land for future operations.

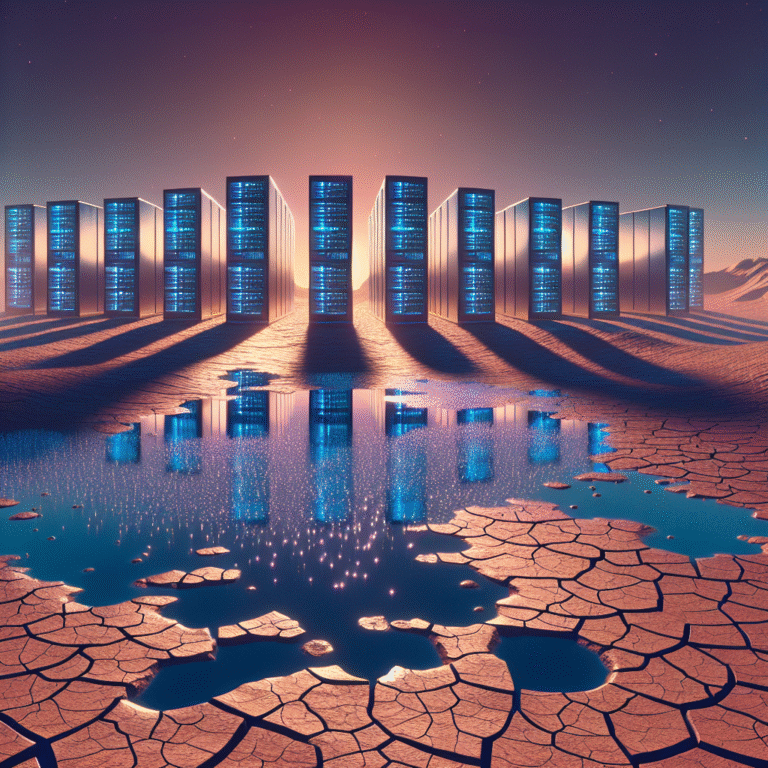

The rapid expansion, however, is largely taking place out of public view and has prompted calls for greater scrutiny. Industry secrecy around the scale, energy consumption, and water needs of these data centers has fueled concern among environmentalists, local residents, and water experts. Public filings suggest that planned data centers in the region have requested nearly six gigawatts of electricity capacity—enough to necessitate a 40% expansion of Nevada’s entire power sector and to consume billions of gallons of water annually. The region’s persistent drought, over-allocated groundwater basins, and erratic precipitation patterns further complicate the sustainability of this growth.

The environmental footprint extends beyond water drawn for direct cooling; data center energy use indirectly increases water needs at power plants, especially where electricity is generated by natural gas or geothermal sources. Advocates for sustainable water management, such as the Great Basin Water Network, warn that unchecked data center expansion could drive regional water policy in unsustainable directions. The Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, whose reservation depends on the Truckee River and Pyramid Lake, is particularly concerned about the loss of water rights and ecological impacts. Past lawsuits and ongoing negotiations have highlighted the tension between economic development and environmental preservation in the area.

In response, some data centers are adopting more water-efficient technologies like air-cooling systems, but these often require more electricity and do not resolve the broader issue of indirect water consumption. Google, for instance, claims to use air-cooling at its facilities and has committed to replenishing more water than it consumes by 2030. Other companies tout closed-loop cooling or leverage treated wastewater to offset potable water use. Still, critics argue that the pace of development and limitations of current water rights threaten to outstrip both local supply and the long-term resiliency of the watershed.

Despite the lucrative influx of tax revenue and construction jobs, there remains broad uncertainty over whether these benefits outweigh the social and environmental costs. Local councils, environmental groups, and tribal leaders continue to debate the future of water use, energy infrastructure, and further data center development. With legal battles looming and climate volatility intensifying, the boom in Nevada’s data center industry foregrounds critical questions about technological growth, environmental justice, and the stewardship of limited natural resources in a rapidly warming West.